Each year, some 170,000 visitors from around the globe make the trek to see it. It made the cover of TIME magazine in 1938-touted as Frank Lloyd Wright’s "most beautiful job"-and was recently added to the UNESCO World Heritage List.

But what, exactly, is the enduring allure of Fallingwater? Yes, the entire house is cantilevered, built on water. It’s impressive. But to reduce it to mere aesthetics would be a disservice. "It’s a multilayered, sensory experience: the feeling on your skin, the eye candy you’re seeing, running your hand across the stone," says Fallingwater director Justin Gunther. "Every sense is engaged, and it enhances the experience of architecture that most places don’t have." To truly appreciate Fallingwater, you have to experience Fallingwater. Thanks to its progressive preservation approach, the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy has transformed the way we interact with the built environment.

It all starts with some windy roads in rural Pennsylvania.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater home has been a catalyst for tourism since it opened for tours in 1964. Most travelers come from more than four hours away and explore other Wright-designed gems in the region.

About an hour and a half outside Pittsburgh, the trees are changing color. You pass through a series of small towns that betray no hint that one of the most prominent homes in architectural history sits right around the bend. On one corner, neon poster board is staked in the ground with a handwritten note: "bingo and pie." Campgrounds and family restaurants dot the road, and you eventually arrive at what feels like a forested state park, complete with a gate house, where cars of architecture enthusiasts line up to tour the property every 15-30 minutes.

It’s not just a home, but a campus. Many don’t realize that Fallingwater preservation efforts support a 5,000-acre reserve and 20 other structures. The visitor center alone comprises pods of buildings branching off the wooden platform, among them a cafe and gift shop. These are the lifelines that fund the preservation efforts of the home-and generate tourism and economic growth for the entire region. But it wasn’t always that way.

Nearly half of Fallingwater’s 5,330 square feet of space are the terraces. The home incorporates nature in every room through views, acoustics, colors, and textures.

They were department store tycoons, the Kaufmanns, who would commission Wright for this weekend home near the Bear Run stream in 1935. Tastemakers and trendsetters, Edgar and Liliane wanted something unique. "They were brave to go with Wright," says Gunther. "Kaufmann saw someone like himself: a force of nature, a strong business person with a strong personality." Ahead of their time, the Kaufmanns would commission some of the greatest architecture in the world (nearly a decade after Fallingwater, the couple tapped Richard Neutra to design the famed Kaufmann House in Palm Springs, California).

Before you even glimpse the residence, you hear it-the sound of, well, falling water. The nature doesn't stop there. Boulders jut into the home, and even the ochre palette is derived from rhododendrons in the landscape. "Nature is the artwork of Fallingwater," as Gunther puts it. It was designed as a retreat from the city, and you can both see and hear nature’s influence from every room in the house.

The Cherokee red corner windows span the verticality of the home, 17 in all. There are no vertical frames in the corners, and you’ll notice the hinges are on the left, allowing the 90-degree angled windows to open like French doors, seamlessly to nature.

The project reignited Wright’s fame. "He entered the most prolific phase of his career after this house. It is a bit of an outlier in architecture, stylistically," says Gunther. "At the time, he’s showing the world a more American, organic world of Modernism." Terraces are as big as the adjacent rooms, and windows have frameless corners so as not to hinder views. "There’s nowhere else like it," says Gunther. "There was never a work like it before, and never one since."

The clients’ son, Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., was instrumental in realizing the impact the home could have. A child during his time at Fallingwater, he went on to study in Vienna, apprentice at Taliesin, and become a founding member of MoMA. After his parents died, Kaufmann, Jr., donated the home to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy for public access.

Fallingwater is located in the southwest mountains of Pennsylvania, known as the Laurel Highlands. Its color palette is derived from the surrounding nature: ochre, inspired by the rhododendrons, and Wright’s signature Cherokee red. He initially wanted the parapets to be donned in gold leaf, but the owners rejected the idea.

Thanks to his foresight, today I get to enjoy brunch on the Fallingwater terrace and see what Gunther means when he described Kaufmann, Jr. as "forward-thinking in how you should operate a public site." It’s one of the many opportunities at Fallingwater that allow you to experience the architecture as it was intended. My group consists mainly of design buffs, people who have come to indulge, linger, and take in one of the most famous homes in the world. It’s not about the food, and sure, it comes with a price tag, but the experience removes you from the mechanism of repeating tours, allowing you to appreciate the siting that could not have occurred anywhere else in the world.

Husband-and-wife architects from New York are here with their son. They’ve wanted to visit for years but had to wait until he could meet the age requirements. That balance of access and preservation is something all public sites must wrestle with-not to mention competing for the interest of youth who have modern-day distractions.

Gunther is addressing that head-on through creative programming, abandoning the sterile, "shoe bootie" model. "The house has a unique ability to connect with just about anyone," says Gunther. "It’s accessible. Other works take more to understand because they’re not tied to something universal, which is nature. You could be six years old or 96, and you’ll find something you can connect with."

The living room of Fallingwater presents a bevy of textures inspired by the outdoors. The floor finish carries just enough sheen to look wet, akin to the rock outside. All the stone used was quarried from the land. Everywhere you look, you're connected to nature: you hear it, you smell it, and you feel it in every room.

One way the site is working to appeal to future generations is through its immersive design residency. In collaboration with Chatham University in Pittsburgh, the Conservancy is helping students better understand virtual reality and augmented reality. "They come here, disconnect from technology, and use principles of organic architecture," says Gunther. "They have alone time to explore, hands-on, how to affect architecture-the basis of UX."

In addition, Fallingwater offers an artist-in-residence program, local library visits, workshops, and internships in everything from education to preservation, collection, and landscape. Further supporting Kaufmann, Jr.’s ideas of access, the Wright in Your Own Backyard program collects donations to provide free transportation and admission for local students. "I worry about relevance," says Gunther. "There’s a timelessness here, even though it’s nearly 100 years old. It keeps me up at night-wondering how it will remain relevant for younger generations."

Polymath Park is home to two Frank Lloyd Wright buildings and two by apprentice Peter Berndson. Owners Tom and Heather Papinchak offer wine tours, progressive dinner tours, and overnight stays in the home for a shift toward experiential architecture.

About 20 miles down the road, Heather and Tom Papinchak have similar concerns. The husband-and-wife duo operate Polymath Park-a collection of homes by Frank Lloyd Wright and his apprentice Peter Berndston-made available to the public for lodging and tours.

We’re sitting at Treetops, the onsite restaurant and birthplace of Polymath Park, where guests ascend one flight of stairs to dine among, quite fittingly, a lush tree canopy. We’re discussing kids and technology, or rather, how this retreat serves as its antidote. "This tool that connects you to everybody is what isolates everybody," says Heather, who doubles as the restaurant’s chef. At night, it’s rather enchanting to dine on the deck among the illuminated forest. Although it’s an upscale menu, and Heather makes the most tender steak you’ve ever had, there’s no pretense here. From the restaurant to the tours, they run a small operation that’s a true labor of love for the whole staff. When they purchased this building in 2000, the Papinchaks simply knew it as home, the place in the woods where they would raise their two daughters. Little did they know that three years later, they would buy the adjacent land-and rewrite architectural history. "Our goal is inspiring younger generations, people’s lives, through hands-on learning, through architecture and nature. We could have TVs and WiFi, but we decided to take the opposite road."

Mäntylä is the most recent addition to Polymath Park. The Papinchaks disassembled it in Minnesota and relocated the property to its new home among Wright's other works. The driveway is a long, dirt road that allows guests to reconnect with nature.

That opposite road is aptly named Usonian Drive. It’s a whopping 130 acres and originally held just the two Berndston properties. After purchasing the land and merely considering preservation work, Heather and Tom would later come across the opportunity to acquire and painstakingly relocate Wright’s Duncan House and, most recently, Mäntylä, starting a movement that has disrupted the way we interact with architecture. So we stayed the night.

It’s raining at Mäntylä. Just outside the master bedroom, the iconic Cherokee-red concrete floor continues seamlessly inside and out beneath a floor-to-ceiling glass door. I’ve never heard nature more clearly. Maybe it’s the acoustics of the home. Maybe it’s because there’s not a cacophony of devices plugged in, but the pitter-patter of rain is as clear as a bell. The hallway is narrow, the ceilings are low, and the palette is warm, focusing your attention even more on the home’s simple materiality and its acoustics. You can’t help but wonder how people passed the time when technology wasn’t omnipresent, and then you discover the books.

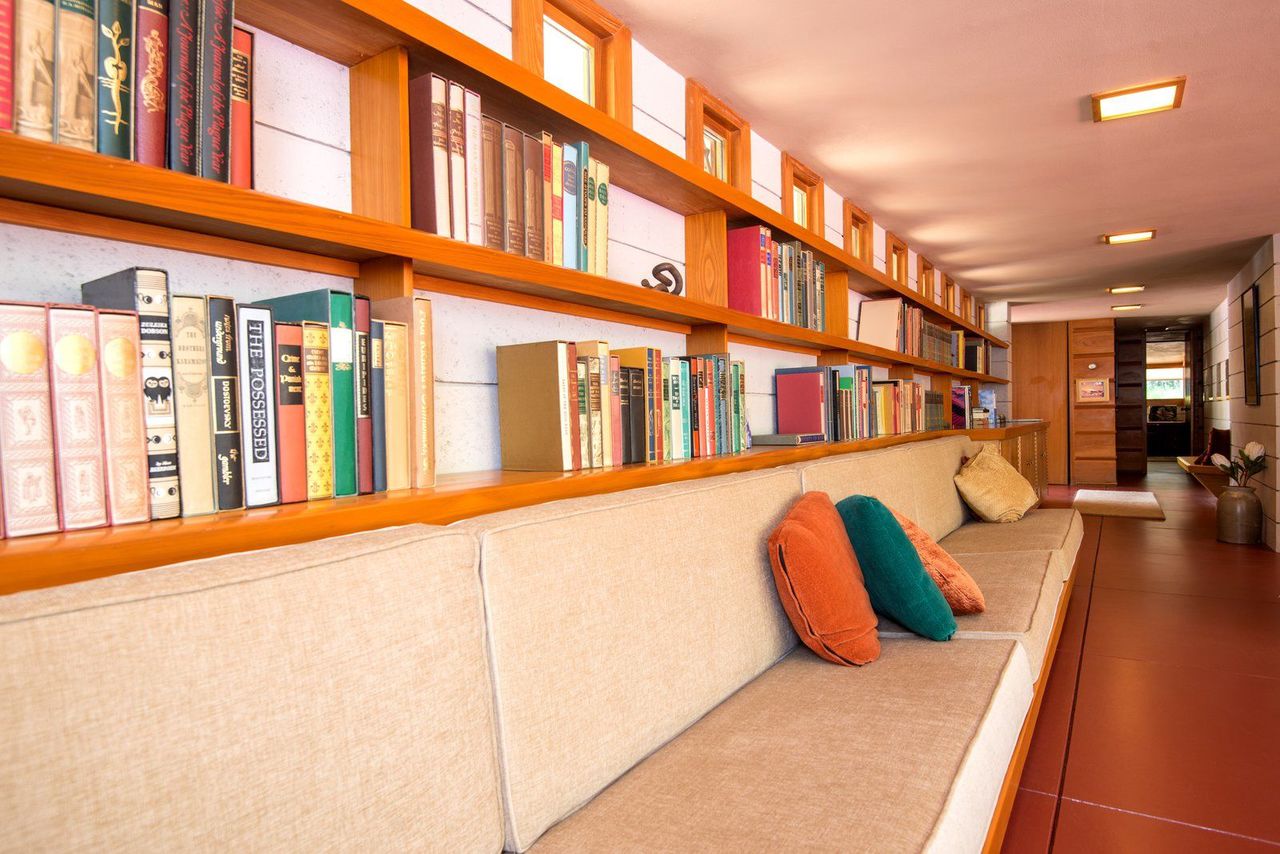

Built-in sofas and shelves, designed by Wright, line the walls of every room in Mäntylä. The books are the original collection, donated by the McKinney family.

Hundreds of rare and first-edition books grace the built-in shelves, which run alongside a built-in sofa. You’re tucked under the shelves lined with the home’s original library, donated generously (along with the artwork and Wright-designed furniture) by the McKinney family. It feels wrong to touch the pages, but it’s exactly what the Papinchaks encourage you to do. "I want to be the opposite, within reason," says Tom. "Not be abusive, but Wright designed these houses to live. It’s concrete floors and walls, so why not enjoy them? You can’t enjoy a thunderstorm or sunsets on a tour, or a hummingbird coming to the window. Nature comes alive in the evening. Nature sounds are all around you-that’s the best part of the house."

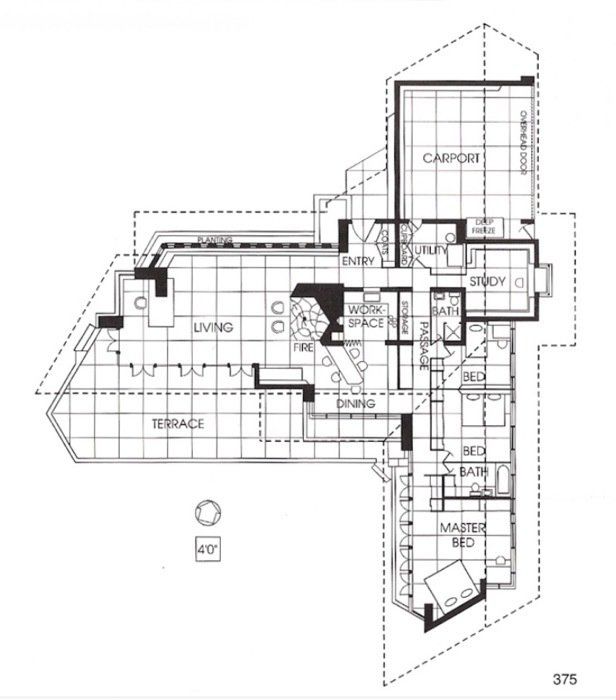

Tom was right. I’ve forgotten I’m in the woods in rural Pennsylvania, surrounded by the sounds of wildlife with not a single other building or human in sight. Mäntylä was designed in Wright’s Usonian fashion, with the living area in an L-shape. The outward-facing facade is private, all concrete block with a simple, yet pleasing mortar pattern. On the interior of the L, the more private side of the home, walls are glass. At one end is the master bedroom with a bed strategically angled for a view of the entire house. Alongside that bed is a control panel with 20 or so unmarked buttons, which I learn operate every light inside and outside the home.

It's hard to find a right angle in the Mäntylä home. With its strategic angling, the master bed looks out onto the entire house. Next to the bed is a control panel that operates every light of the home, indoor and out.

The kitchen is in the middle of the home but manages to hide in plain view. It’s closed on three sides, with soaring storage above. Short of the intermittent concrete blocks offering a peek into the foyer, it feels encapsulating. Tom sourced a vintage wall oven, and the red countertops appear to exactly match the Cherokee-red floors-where I find a frog in the middle of the night. I must have left the door cracked when exploring the sprawling patio. It’s easy to do when indoor/outdoor living comes so effortlessly. That night, I bolt back down the narrow passage to the master bedroom. And I press every single button on that control panel.

The U-shaped kitchen is partially enclosed in the middle of the home. The concrete reveals look out onto the foyer.

Heather tells me there is a pond next to the house and chuckles when I tell her about my night. That’s life at Polymath Park for the Papinchaks. They’re down-to-earth, family folks, passionate about education and the connection between nature and architecture. The same person who works in the kitchen also gives tours-and previously, worked around the clock to dismantle and relocate Mäntylä. You won’t find 1,000-thread-count sheets here or luxury soaps, but you will find immense passion, quietude, and above all, access. "I’d rather you have an experience that feels like you’re not being rushed through a property," says Heather. "People who stay, they value the experience and the structures, and that’s where preservation begins."

The same concrete facade is found inside the home, as is the Cherokee red floor, which expands onto the patio.

Admittedly, it’s a radical approach. The Papinchaks afford us a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to experience architecture, complete with original furnishings, but at what cost to its future? How do you ensure that history is preserved for our children and theirs?

"Heather and Tom are giving new homes to Wright architecture-it’s another step toward preserving Wright’s legacy," says Gunther. Back at Fallingwater, he continues to wax on about Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., and his intent for Fallingwater as a public site. "He wanted the house to continue to live," he says. "He didn’t want it frozen in time." It’s why they offer open-door tours, where visitors can roam freely, that welcome everyone from heritage seekers to enthusiasts to biker gangs cruising through the Highlands. Says Gunther, "We think often, ‘How did the Kaufmanns live?’ You have fun, relax, have parties, share moments with friends. That’s the idea of our brunch tours and our sunset tours. We want people to experience what Kaufmanns would have." Hopefully, sans frog.

Frank Lloyd Wright designed the dining table, which is built into the kitchen. Its chairs are low and comfortable. To the left, a wall of glass offers expansive nature views.

Clerestory windows at the Mäntylä house have beautiful, detailed wood carvings. The owners originally requested that Wright include a garage, as they lived in Minnesota. The compromise was the enclosed carport to the left.

The inner "L" of the home is the private side that looks onto the terrace and woods. Glass flanks these walls, while the outer "L" is the public side, closed off with concrete block.

![A Tranquil Jungle House That Incorporates Japanese Ethos [Video]](https://asean2.ainewslabs.com/images/22/08/b-2ennetkmmnn_t.jpg)